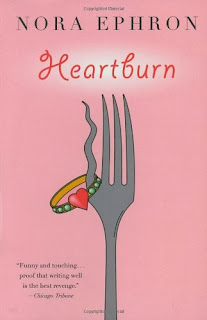

HEARTBURN — “’Tis the season to be jolly.” It’s

also the season to miss people. Nora Ephron is someone to be missed. She could

make us laugh at our necks, and at almost anything. Her novel, Heartburn (a barely fictionalized

account of the end of her own marriage), even manages to make us laugh at

divorce. Why she turns a sad, disturbing, and even enraging reality funny is an

interesting question.

Divorce isn’t a laughing matter.

For Rachel Samstat, Heartburn’s

betrayed wife, it’s certainly not funny that her husband’s having an affair

with a woman who just came to dinner and asked for her carrot cake recipe.

Especially when, not suspecting anything remotely of the kind, she willingly

gives it to her. A laugh can be a good thing. Laughter is also a way of

avoiding tears. Rachel cries, but fights it. As her therapist says: “She makes

jokes even when she feels terrible.”

Francine Prose’s review of The Most of Nora Ephron (2013) in the

November 21, 2013 issue of New York

Review of Books raises some interesting questions about the use of humor in

Heartburn:

What is lost when a fictional character’s pain is instantly dissipated by a joke? If we can’t feel sorry for Rachel, we run the risk of not feeling anything at all. We understand that she has been wounded by her husband’s infidelity, but the speed with which Ephron throws her heroine the life preserver of a wicked retort may suggest that what has been sacrificed is not merely plausibility, but emotional truth.

Prose is right. As readers, we’re

neither allowed to feel or learn a thing or two about the emotional travails of

divorce. But, although Heartburn is a

roman a clef of sorts, it’s not Nora Ephron’s whole story. In her 2010 essay The D Word (HuffPost, March 8, 2010),

Ephron admits to all the feelings Heartburn’s

heroine avoids:

It’s a very funny book, but it wasn’t funny at the time. I was insane with grief. My heart was broken. I was terrified about what was going to happen to my children and me. I felt gas-lighted, and idiotic, and completely mortified. … I was angry and hurt and shocked … I survived. My religion is Get Over It. I turned it into a rollicking story. I wrote a novel. I bought a house with the money from the novel.

Yes, Ephron had some pretty

painful feelings. But, what is this

pull-yourself-up-by-your-own-bootstraps “Get Over It” philosophy actually meant

to accomplish? She’s avoiding pity. She’d rather we laugh at her than pity her. Why pity, though? Does she think we’d see her just as “idiotic” as she

sees herself? Does she believe there’s something shameful about what happened

to her? Does she feel it’s her fault? Most importantly, does she not trust that

most people would empathize and not judge?

Because of Ephron’s inimitable use

of humor, I’m not sure she meant “Get Over It” as coldly as it sounds. But, as

a psychoanalyst, I must say that the “Get Over It” philosophy is too harsh a condemnation

of the feelings involved in divorce. Hurt, anger, terror, and grief are normal.

What these feelings really need is not

to be quickly dismissed, but given time and a place to be felt, spoken about

openly, understood, and resolved. Especially anger. If someone is too afraid to

direct the anger where it really belongs, they’re very likely left with

terrible and undeserved self-indictments.

Rachel Samset’s method of laughing

off her feelings, or being all too self-sacrificing instead of angry, could

leave a woman quite stuck in a mire of self-hatred and self-blame. Yet, I can’t

put Nora Ephron in that category. Writing this delightfully tongue-in-cheek

novel exposing her husband’s infidelity in all its reprehensible colors had to

be a most satisfying bit of revenge. Better yet, isn’t Heartburn a creative use of anger that actually might have freed

her?

No comments:

Post a Comment